Memory-Images

Pablo Pijnappel

…and the memory of the great mirrors inside the waiting areas, mirrors that already functioned as quasi-cinemas: to see yourself in them was to see yourself in a film; to see yourself in them was an invitation to enter the reality of the image and to live an experience similar to that little girl Alice: to let yourself fall into Wonderland, and roam around in the land of mirrors.

(José Carlos Avellar in Dust and Palaces: 100 years of Cinemas in Rio de Janeiro by Alice Gonzaga; Record Funarte, 1996)

Picture a very early Sunday morning on the shores of Copacabana. During his daily jog on the beach, a local sees a yellowy glimmer of sunlight reflecting from the inside of a bottle being washed ashore. It has the appearance of one of those message-bottles tossed by the survivor of a shipwreck. He stops, picks it up, and uncorks it. With his right eye he proceeds to peek inside, and is offered in return his own eye looking back at him from the bottom. He drops the bottle on the wet sand and continues running, or he flees in dismay. There are opposing views concerning this part of the story.

Through much of human history, the only specular surfaces were those of still bodies of water, such as puddles, wells and lakes; recall the myth of Narcissus, for example. There is also evidence that the ancient Greeks already had mirrors made of polished iron and bronze (as Medusa painfully learned), but it took about a thousand years of progress in chemistry to be able to produce mirrors as pristine and clear as crystallized water (and consequently start eradicating mosquito breeding grounds; one can only imagine the number of Greek narcissists stricken with Zika two millennia ago, with Egypt so close to the South).

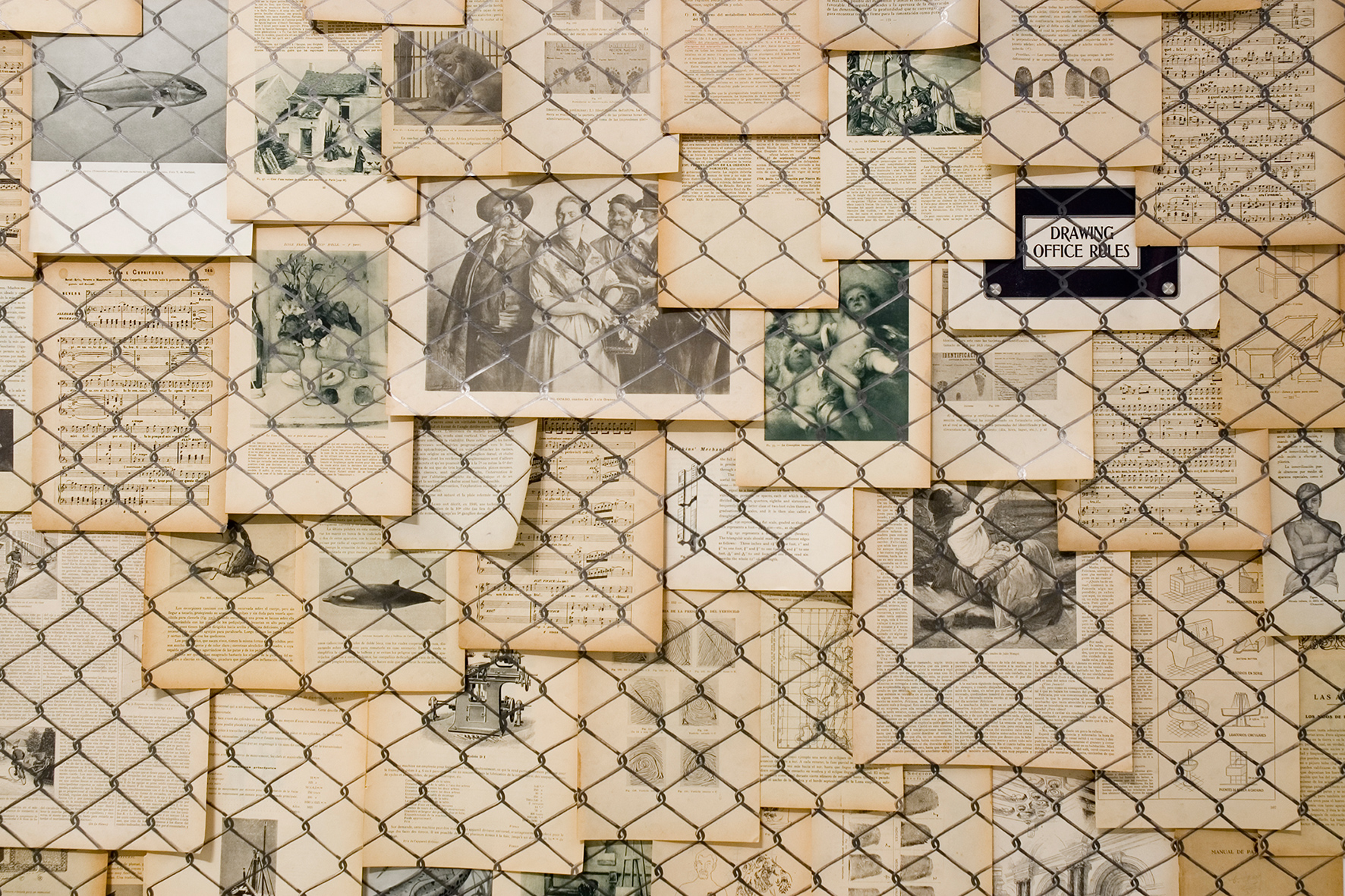

Around 1500 A.D., with the aid of mercury, the melding of silver into glass plates led to the first appearance of something closely resembling our modern mirrors. Still, it took until the 1840s for the mass production of these true specular crystals to be viable. The first photographic negative glass-plates were fabricated around the same time. An improvement over daguerreotypes, which were costly and yielded only a nonreproducible positive image set in metal, the negative glass-plates employed the light sensitivity of the silver grains, together with mercury and common salt, to crystallize an image carried by the light emanating from objects crossing the camera obscura.

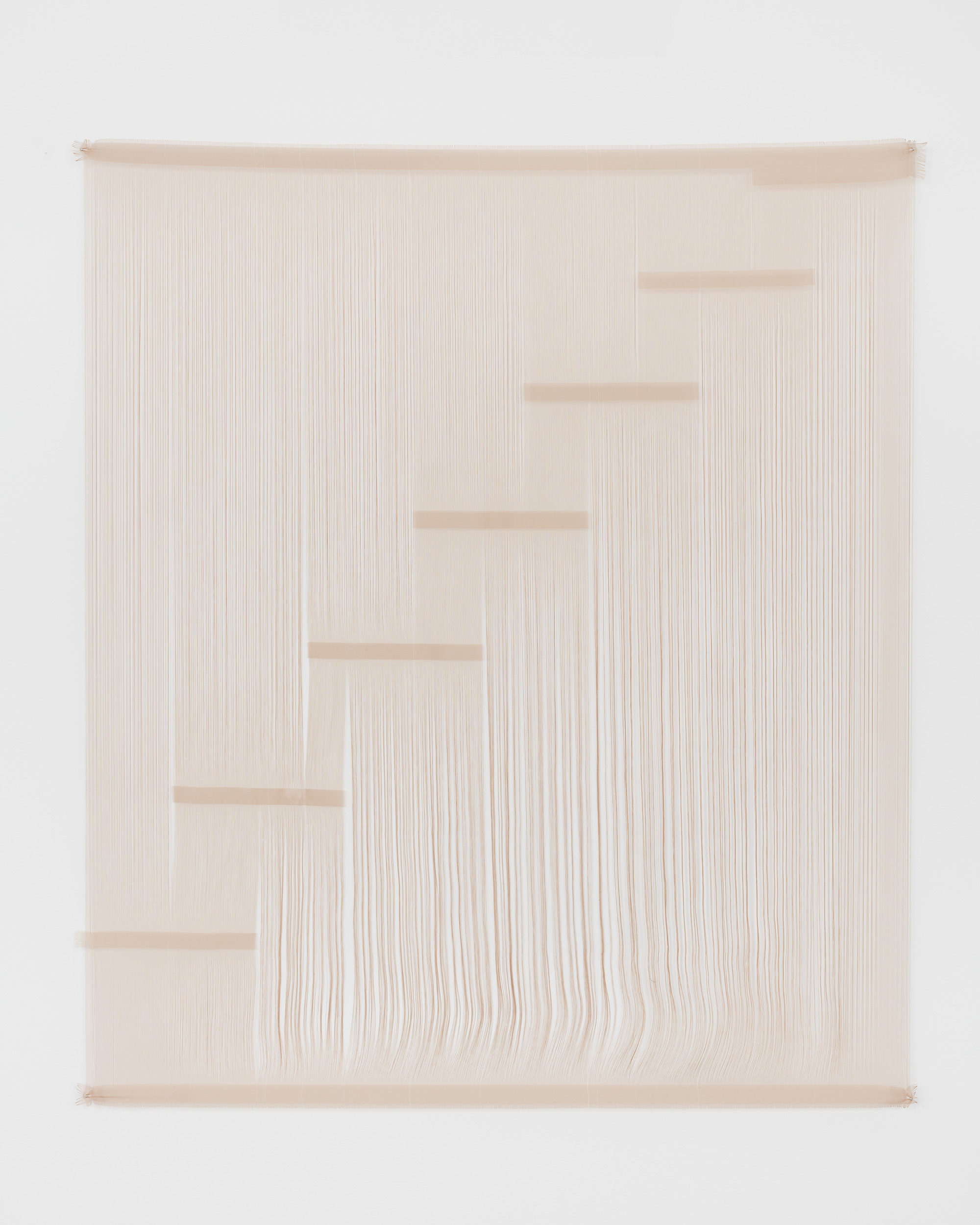

Like a specular image, a photograph is also in principle just a symmetric copy. However, while the mirror’s virtual image is completely congruent, like the backside of a hand-written text on paper, what happens in photography is more akin to what happens when we see ourselves reflected on the surface of a second mirror, i.e. in a reflection of a reflection. Like a photograph, a twice-mirrored image is no longer as reflexive; it turns a first-person point of view into a third-person one, and a subjective stance into an objective one.

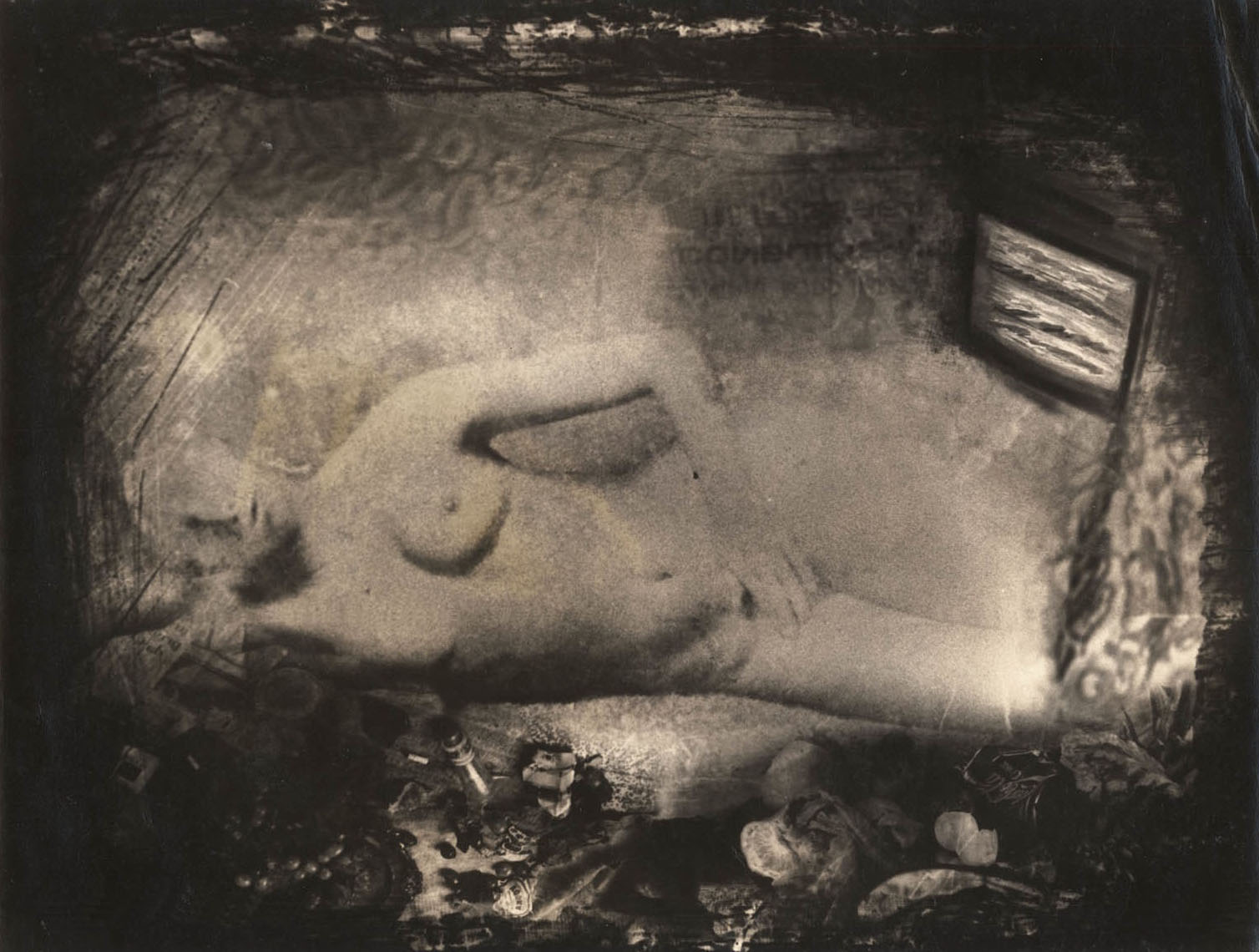

Perhaps more important in photography is the emancipation of the image. In “The Fisherman and His Soul” by Oscar Wilde, a shadow separates itself from its master and does all kind of evil things until the owner manages to sew it back to his feet in the moonlight. Likewise, in photography the total congruence of the copy is lost, making it a reproduction rather than a double. Now, being solely virtual, without a living, real-time link to the real object, it becomes almost an icon or a sign, but not quite. As Barthes was wellaware, a photo remains a denoted message, a soulless sign.

The Amerindians seem to have known this all along. Although they were keen to receive mirrors as presents from the Portuguese, later they reportedly refused to have anthropologists take their photographs, fearing that their souls would be trapped in them. On the notion of a soul-capturing device (or a memoryimage-capturing device, as Bergson could have call it): although the detached objectivity of photographsoften unsettles our recollections, we could say that by freezing the specular image, the photograph also registers time, or rather, that it crystallizes the event, becoming a memory. It was Freud himself who once compared the formation of a memory to an image being reflected across a row of mirrors inside our mental apparatus until reaching the bottom of our unconsciousness, like light trickling down a telescope. This analogy always particularly comforted me since it is exactly when it comes to this horizontal-symmetric congruence that memories often get the best of me.

This happened upon returning to my hometown after having left it many years before. When visiting the building where I lived as a small child, I not only had the sensation that the Rue Tombe-Issoire had grown narrower over the years, but also that the windows of my old apartment were on the wrong side of the street. (Actually, maybe this doesn’t make sense, but whenever I look at a map, the same kind of inversion happens. During the same visit to Paris, I mistook left for right and found myself alongside the walls of a cemetery. Having come to revisit my early years, I ended up where I could hypothetically be buried someday, had I not left the city.)

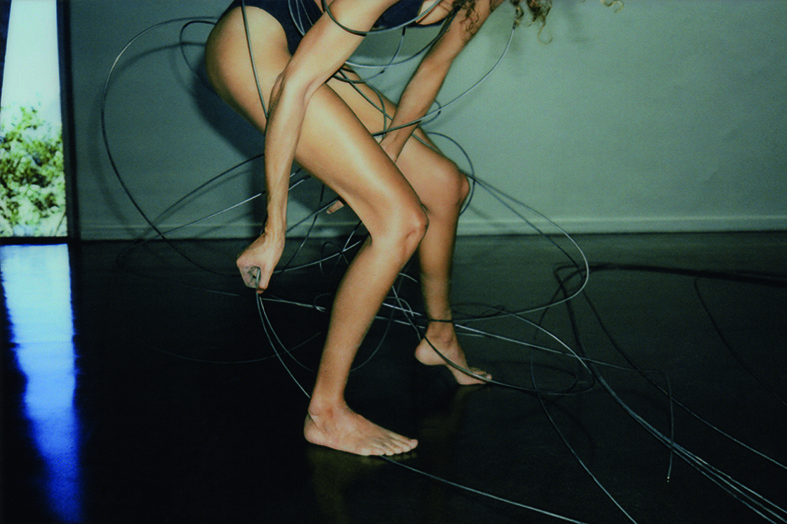

It’s curious how Umberto Eco explains that, in relation to the specular image, our conception of symmetric inversion is always horizontal simply because we are more accustomed to looking into vertical mirrors. He goes on to say that, in contrast, libertines (his word) know very well that to mirror can also mean to create a vertical-symmetric inversion, since they have horizontal mirrors hanging on the ceilings of their bedrooms. This is to say that you can mistake up with down, as well as left with right. (Good thing I’m conservative.)

Sometime ago I returned to Rio, where I grew up, after a long interval without having visited. The tropical colors of the vegetation and mountains felt quite hallucinogenic, and like in Paris before, the proportions of space and of objects felt annoyingly wrong. When I entered my grandmother’s apartment in Copacabana, where I had lived in the last years before moving back to Europe, as soon as I set down my bags I noticed that the walls seemed warmer than I had recalled, and that the paintings hanging on them had grown in number. In my old bedroom, where I spent my haunted teenage years, the carpet was greener and fluffier. Above a desk hung a large mirror which I tried to avoid but inevitably…

Shocked and dazed, feeling as though four years had gone by since I took the cab from the airport, I went down to the street and bought new flip-flops and strode towards the beach. There, sitting on the sand, I was relieved to find that the waves still looked the same. I even think I recognized one or two that splashed with particular foaminess.

Watching a point out at sea where a German cargo ship was floating, I recalled my grandmother telling me about the Rian movie theater, which like many cinemas in the 40s and 50s was built on the waterfront alongside the luxurious casinos and hotels. These cinemas were the first public areas with air-conditioning, giving shelter during matinees to the overweight, the pale, and the travelers too broke to buy a ticket on a ship, much less a plane, bound for Paris, and instead came there to escape the heat and watch a film starring Martine Carol. The Rian’s entire lobby was covered with huge mirrors reflecting the beach, which back then still hadn’t been land filled, and lay only a dozen meters from its entrance. Hence, when you entered the screening room, it was analogous to submerging yourself under the waves and letting yourself be dragged along by the current.