Sala de Espera

Halfway through the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic while catching up in a phone conversation with friend and artist Stefano Faoro, we inevitably ended up reminiscing about our time together as participants of the Jan van Eyck Academy. Our talk moved along the usual thread of how these exchanges tend to go. Nothing out of the ordinary. At the tail end of our conversation, while we shared some of our stories about failed expectations from those days, we attempted to calculate between the two of us the number of years taking part in different art residencies and post-academic programs. Stefano went on to question what was that we got out of it after the realization of having spent the better part of our late twenties and early thirties going through several art institutions, mostly in northern European countries. At that moment we found ourselves with very little to show in matter-of-fact economic terms as well as from the promise of the ensuing opportunities that never seem to fully materialize after participating in what some deem as prestigious art institutions. All of that which was being said was underlined by our apprehension due to the given uncertainties of the immediate future we faced and still do—pandemic-wise, the reality of climate crisis and the imminent political instability as consequence.

The years of experience being inside art institutions, beginning from the effort exerted to be accepted in order to develop one s practice, then the experience of going through them and while in them the many ways of having to learn how to be inside, has in several ways informed the development of my practice as an artist—for the good or the bad. Making this publication has been an attempt at uncovering and facing, rather than avoiding, the tensions that are part of what defines the relationship between artists and art institutions, and especially at a time when most art institutions themselves are under the pressure of austerity politics. In this publication I have documented the different stages of the development of the doctoral research, The Artist Job Description: A Practice Led Artistic Research For the Employment of the Artist, as an Artist, Inside the Art Institution, all the while exposing vital moments of learning that as a consequence has led to the transformation of my artistic practice. One of these moments was the refusal to frame the informal kitchen at the Jan van Eyck Academy into an artwork, which allowed the act of running a kitchen out of an artist studio to remain a structural proposal in relation to the institution. Consequently, the act of refusal triggered the transformation of my artistic practice into an institutional practice. An institutional practice that is indebted to artistic thinking and subsequently looks for non-administrative ways of organizing within administrative structures to become a speculation into the plasticity of institutional structures as a potential for co-creation between artists and institutions.

In order to chart both the development of the research and the aforementioned transformation, I made use of public moments to generate textual material for this publication. I deliberately chose to work with transcribed public presentations and conversations to Hi keep text close to the spoken word, as a way to expose important moments of learning to the reader. With the episode of the informal kitchen in addition to the transcribed artist talk, it was important to reenact that experience in a conversation with others to broaden the understanding of the events leading up to and the consequences of the provisional kitchen. The publication then moves on to the editorial project Samba Shiva, via another transcribed talk, it rearticulates some of the lessons collected from the experience with the informal kitchen into a new institutional setting of the Instituto Moreira Salles. It was personally important to me in moving forward and making sure that my practice would relate non-antagonistically to the new institution—hopefully without losing its critical edge in the process.

What I did bring over from the episode of the informal kitchen to the editorial project Samba Shiva, was a better understanding of the space and the role afforded to artists and the expectations placed upon artists by institutions. This space/role in which an individual artist’s whim is incorporated so long as the expectations of an artistic outcome from the artist are met and/or made presentable. So, a way to go about it was to occupy this space/role but instead of looking to thrive in it, I had to learn to disappoint the institution’s expectations and to cope with the flip side of the disappointment myself. In a counterintuitive manner, this process of challenging the institutional protocols opened a way to experiment and test the invisible boundaries of that said space/ role within the institution. In Maastricht, it came about challenging the new institutional order defined by larger neoliberal economic forces that manifested itself as the recently renovated artist studio. This I did by not using the studio for art production and by refusing the institution’s suggestion of presenting the informal kitchen as an artwork in relation to the frame of their public pro- 14( gram open studios. With Samba Shiva, it was not so much about disappointing the institution itself as the collaboration with the institution opened up the space for dialogue. I like to think that this collaboration was able to challenge to a certain degree the mechanism of legitimization that institutional frames are traditionally designed to emphasize. This was achieved in part by rethinking authorship, avoiding complete appropriation of what is made outside of the professional art field, and by giving due credit to various collaborators. As a result, re-ascribing the potential visibility given by a prestigious art grant and certain beliefs surrounding the relationship between authorship and the artist.

Being able to and willing to play with certain preconceptions of what being an artist entails and what constitutes an art practice, was a necessary step towards gaining some leverage when negotiating with institutions — testing the aforementioned potential plasticity of the institution. On the other hand, while experimenting with aspects of this research in the editorial project Samba Shiva, I was made aware of the consequences of what was proposed with this research in relation to staff and employees of institutions burdened with additional work required to review and perhaps modify established institutional procedures. At that moment, from the position in which I came into the institution, I was forced to reflect on the ramifications of intervening in institutional procedure, and used this insight for my own employment as an artist-researcher developing a PhD in the Arts.

Being employed part-time at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp played an important role in the development of the research, as I was able to root myself in an institution before going into another to research. The four-year period provided the economic stability that in turn allowed me the time, headspace,and resources to dedicate myself to the research and take chances with it. At a later moment, once aware and made comfortable inside an educational setting, I began to involve myself and engage in different activities pertaining to teaching, advising and others. And to look at the liberty that I was afforded as an artist-researcher to raise discussion surrounding politics, race, class, and gender which in my opinion the institution did not address with the urgency these issues demand. One such engagement is the organization of the research seminar Description Changes, The Artist Job Description, which follows the first part of this publication. With the seminar I aimed to gather peers in order to think and to work together towards strategies to negotiate other ways of entry and being in art institutions. Perhaps, more importantly, to have my peers remind me that to be invested in an institution does not have to always render into attitudes that reaffirm the institution, in some cases, it can also come in the form of a complaint.

[…] To conclude this afterword, I would like to consider once more what it meant to have gone through these institutions over the years, if not for a palpable return, then perhaps an understanding of the role of artists inside art institutions that is on one hand critical and the other generative. An understanding that is sensitive ^1 to the potential knowledge of the artist concerning how things are done inside the art institution. Folded into that understanding is the awareness that the working conditions for artists, more often than not, correlates to how institutions respond when under the pressure of imminent budget cuts or otherwise. With that being said, how do we artists claim a certain degree of autonomy inside and in relation to these institutions that is necessary to continue to develop our practices, make a living and contribute towards a communal responsibility of preserving the diversity for the healthy functioning of the art field?

Preceito Fundamental

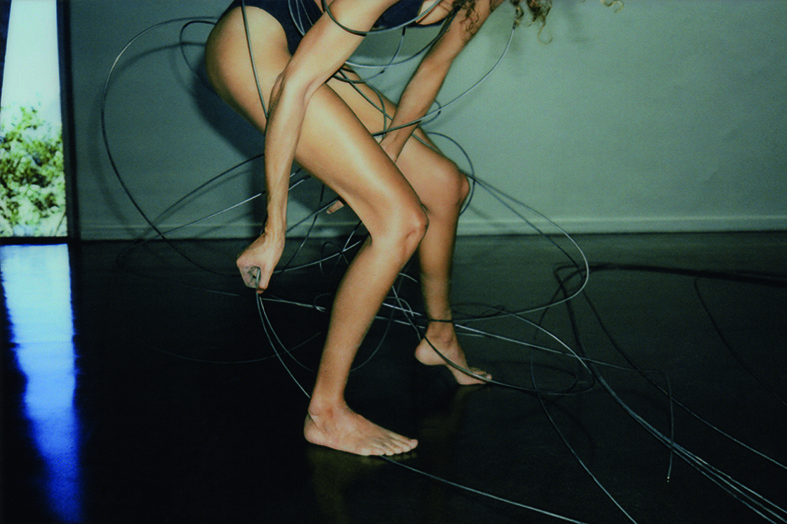

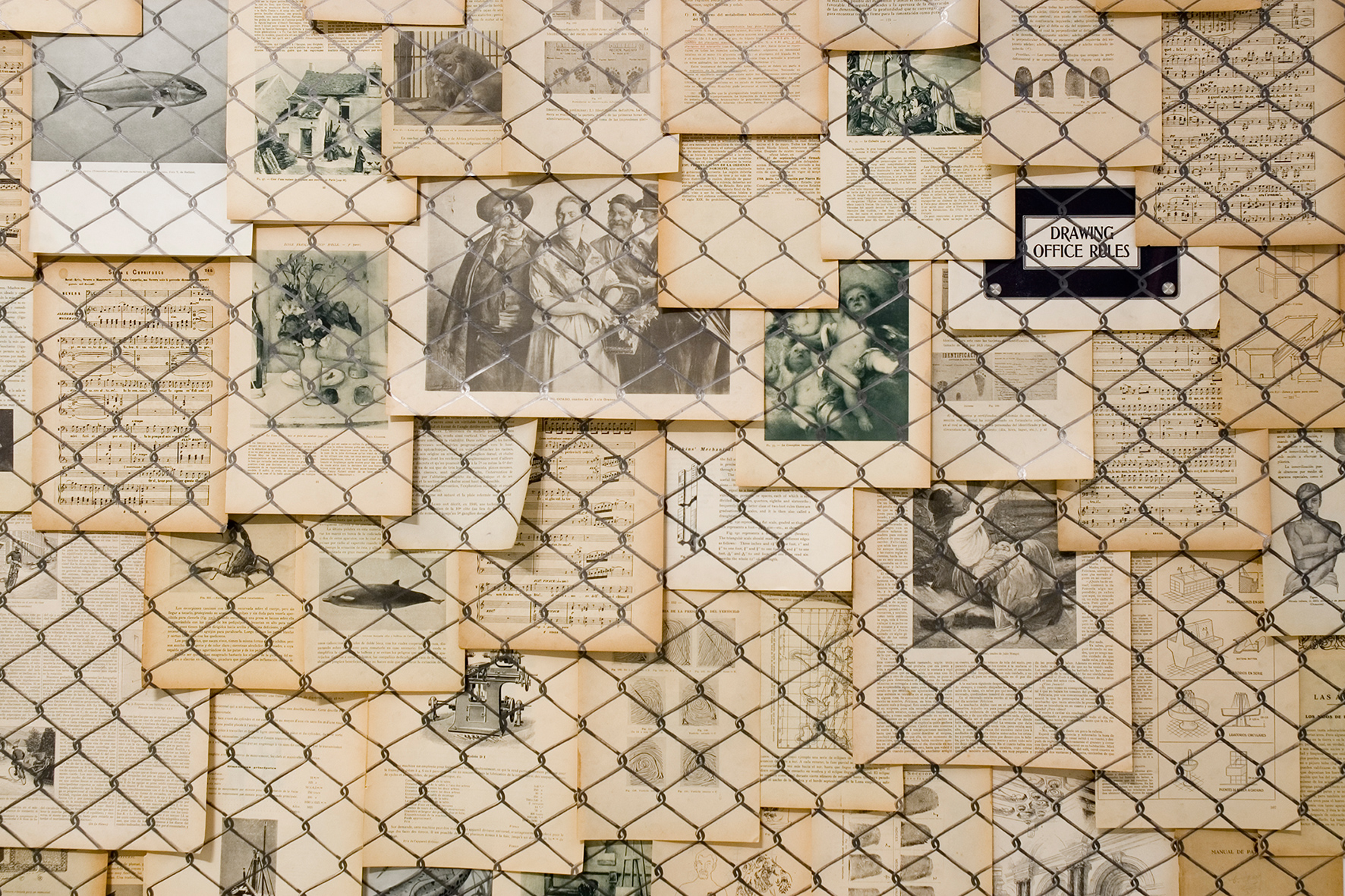

“Preceitos fundamentais” representam direitos civis que deveriam ser constitucionalmente protegidos, englobando vida, liberdade e propriedade. Esses direitos inalienáveis incluem a proteção contra tratamentos desumanos e degradantes, juntamente com a garantia de liberdade de expressão, manifestação de pensamento e igualdade na sociedade. No entanto, somos diariamente confrontadas com questionamentos sobre nossa liberdade em relação aos nossos próprios corpos e à capacidade de expressar nossas ideias, muitas vezes condicionadas pelas normas sociais que nos cercam.

A exposição que inaugura no próximo dia 28 de outubro, no Espaço CAMA em São Paulo, reúne trabalhos de 15 artistas mulheres e não binárias com o intuito de explorar temas como a intersecção entre expressão, sexualidade, escolhas religiosas e o direito à individualidade. “Apesar desses temas serem recorrentes nas pautas sociais e artísticas, pouco mudou na prática. Essas pessoas continuam enfrentando as mesmas violências que datam séculos”, afirma Maíra Marques, co-fundadora da plataforma Comadre que assina a curadoria da exposição, Gabriela Davies, sua parceira, complementa, “O nome da exposição, Preceito Fundamental, inspirado pela movimentação da ADPF442, reconhece que o direito sobre o corpo é concreto e não deve ser objeto de discussão.

A mostra pretende incitar a reflexão sobre as complexas interações entre autonomia, corpo e sociedade, proporcionando um espaço para explorar esses temas por meio da arte. Para isso, conta com a participação de Ana Clara Tito, Anna Costa e Silva & Nanda Félix, Ateliê Transmoras, Carla Santana, Claudia Jaguaribe, Geoneide Brandão, Giovanna Langone, Guler Ates, Lyz Parayzo, Márcia X, Maria Antonia, Polvo de Gallina Negra, Santarosa Barreto e Thix.

Por meio da venda das obras na exposição, a Comadre e o Espaço Cama destinarão uma parte dos recursos ao Projeto Vivas, organização sem fins lucrativos que auxilia mulheres e pessoas com a capacidade de engravidar a acessarem serviços de aborto legal, tanto no Brasil quanto no exterior.

Escada D’água

Doispontozero

Deus e o diabo no sertão carioca

Labirintos vivos

Corpos líquidos, almas sólidas

texto Catarina Duncan

“In the beginning we were all the same living being, we shared the same body and the same experience, since then things have not changed so much, we have multiplied the forms and ways of existing, but even today we are the same life. For millions of years this life has been transmitted from body to body.”

(Emanuele Coccia, Metamorphoses, 2020, p. 13).

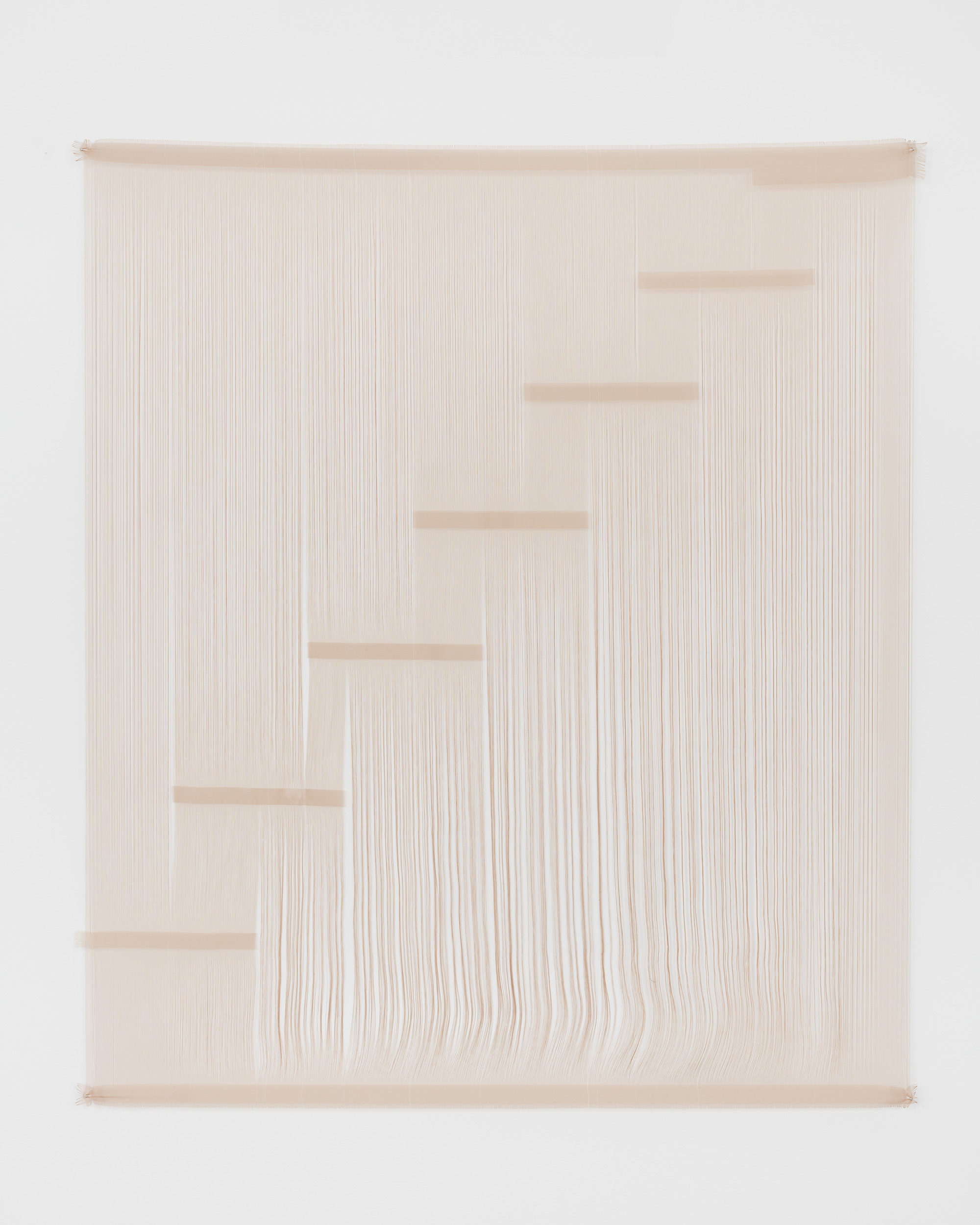

‘Liquid bodies, solid souls’, crosses fundamentals of nature, scientific research and forms of enchantment. Broadening our gaze on the notion of matter, we understand that what seems fixed, rigid and stable appears light, porous and vulnerable.

This exhibition works with three axes – matter, idea and invisible – in search of an understanding of the human condition as part of a multiple and changing ecosystem. Romain Dumesnil’s works operate between the contemporary and the ancestral, between metal and clay, between algorithm and choice, to draw, dream and imagine new landscapes. The works come together as a landscape, a set that completes itself forming a collective territory.

The combination of these axes comments on the possibilities of producing life, in a continuous research on forms of creation. The ‘Labirinto’ series is composed of paintings made of mixtures of minerals based on algorithmic guidelines of variations in the atmospheric magnetic field. These invisible factors that cross us are embodied here as matter.

Two recent paintings, entitled ‘Apicum’, made with clay and natural pigments, are also presented, pointing out the principles of creation. In several cosmologies, clay is recognized as the first form of life, participating in the very elaboration of the human form. By creating these images with clay, using the earth as paint, Dumesnil refers to the primordial ways of transforming matter. It is the first substance that gives us form and enables us to exist in the material world. Api-cum means marsh of salted water in Tupi Guarani, and refers to a plain capable of absorbing and storing carbon dioxide.

We are facing a planetary phenomenon of climate and structural change, since we distance ourselves from the idea of ‘nature’. By understanding that we are nature and that we are part of collective systems, we can see this exhibition as a dialogue between beings that affect and transform each other.

The works ‘Lapso’ and ‘Desvio’ are conversations that structure two magnetized vol-canic stones that levitate. While ‘Elevation’ also proposes a negotiation with matter, in this case helium gas, recognizing the invisible materiality of one of the most present chemical elements in the universe. This is not a challenge to nature but an exchange, it is up to us here to realize and accept that we do not control anything, but live in relation to everything.

The quote above, from Coccia’s book ‘Metamorphoses’ situates us in relation to this multiplicity from the perspective that we are all made of the same matter. This shared primordial moment connects this exhibition, which shapes the invisible by dreaming non-existent landscapes. The work ‘Rift’, made by an aluminum branch that scratches the wall, merges the vegetal and mineral body, once again, diluting the separation between nature and culture, between what we are and what we produce.

Climate change does not affect all peoples in the same way, we do not experience the world in the same way. According to Bruno Latour, our sense of identity is falsely given by a defense of borders: “From the soil, the Terrestrial inherits materiality, heterogeneity, thickness, dust, humus… The soil, in the new proposed sense, does not may be appropriate. We belong to him; he belongs to no one.” The purple pigment ex-posed in islands on the exhibition floor leads us in a choreographic movement, where not all paths give way, not all bodies have the same experience and the soil starts to have agency over us.

The feeling of being led and guided by a topography crosses us to realize, once again, that we will not always have control. Similar to the feeling of the work ‘Dance’, in which larvae are positioned in a collective movement.

The stable soil of the Holocene is no longer guaranteed. The work ‘Psychic Forest’ emits smoke that comes out of cracks in the floor, emanating the steam of plants with psychoactive qualities that can be used medicinally for healing or illness. When ente-ring this space, your body will be affected.

What the ongoing environmental catastrophe poses to us as a challenge is: how to manage with the elements we have and no longer insist on the logic of escape. Seeking a qualified existence, in relation to matter and the beings with whom we live. The works in ‘Liquid bodies, solid souls’ are like a beacon to illuminate what is already happening and we often do not notice. In addition to our fields of vision, we activate a sensory and sensitive field that reminds us that life is not static, it is not “finished”, and therefore, every end is part of a beginning.

Bibliography

– Coccia, Emanuele. Metamorphoses, ed. Dantes.

– Lima Barreto, João Paulo. WAIMAHSÃ: Fishes and Humans, ed. UFAM

– Latour, Bruno. Where to land?. ed. Bazar do Tempo

– Ferdinand, Malcolm. Decolonial ecology, ed. UBU

Palimpsesto Sentido

CORPO E ALMA

text by Eder Chiodetto

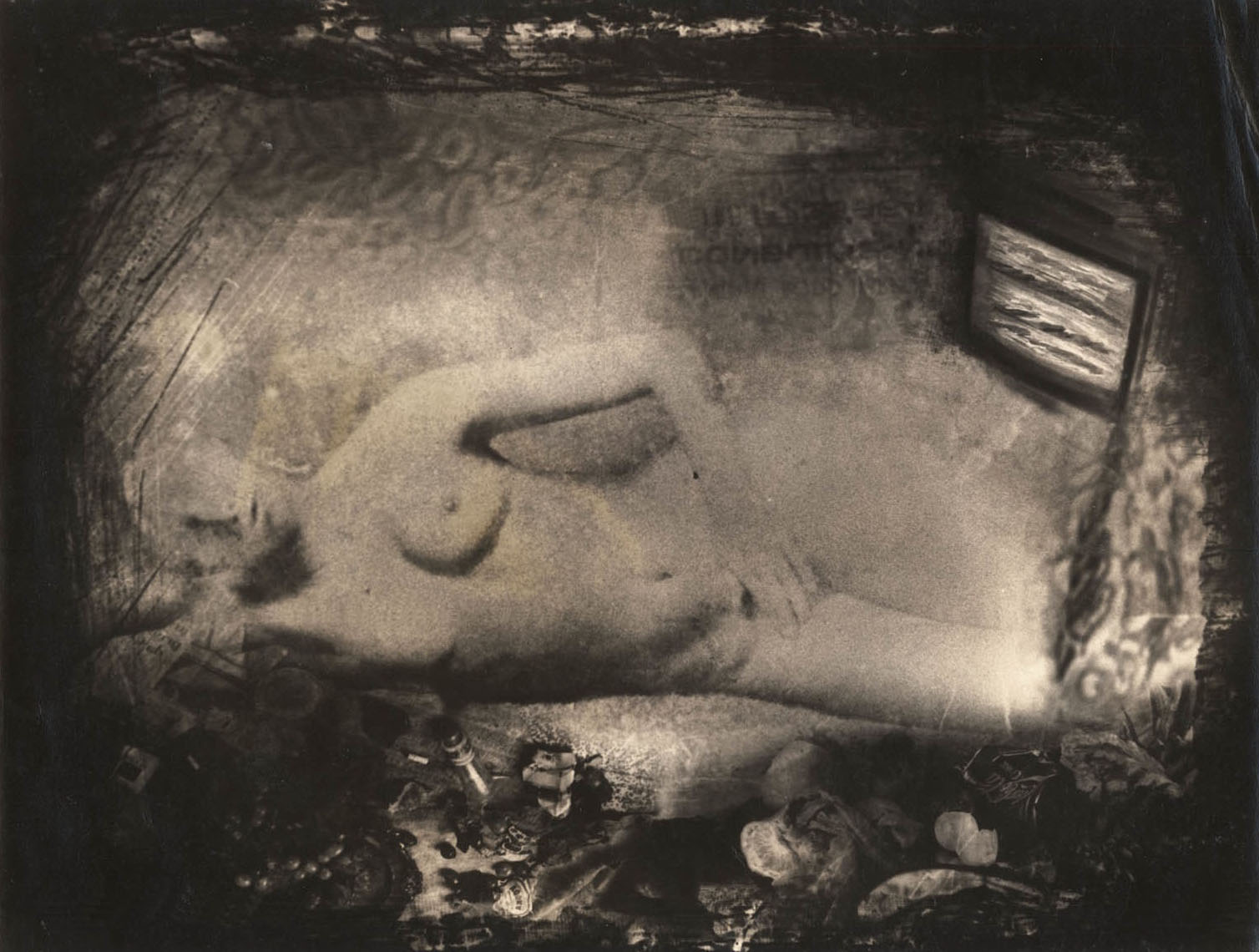

Eustáquio Neves has the rebellious nature of artists who, when appropriating an artistic language for their expression, do so in a way that violates previously imposed rules in order to expand its possibilities. In this way, within his creative experimentation laboratory, he contributes in a powerful way so that photography gains renewed configurations.

Therefore, Neves is an artist who not only uses the language repertoire to enhance his speech and poetics, but acts as someone who reinvents language itself, expanding its limits, and leaving such an experience as a precious legacy for the history of photography.

Much of Eustáquio’s work is dedicated to reflecting on the structural racism that continues to echo, until today, in a perverse way in Brazilian society and around the world since the ill-fated and violent advent of slavery imposed on African peoples. The history books that circulate among elementary school students, in general, soften and do not go deeply into the atrocities perpetrated against enslaved people in Brazil. Since the 1980s, Eustáquio’s work has become a pioneer in combating these false truths that are perpetuated.

His experiments, which transform the surface of the photographic support into intricate layers, can be read as a strategy for dismantling the historical process of constructing narratives that are ideologically oriented and always told from the perspective of those in power.

This exhibition held by Cavalo art gallery presents some specific icons from the artist’s production, most prominently the images from the Objectification of the Body series. It was images of naked women, which he studied in Renaissance paintings, that led the artist to think about the marketing uses of the female body in today’s world, invariably objectified and sexualized by advertising. Using a black model, an exception in these campaigns, Eustáquio weaves a necessary critical commentary that amalgamates machismo and racism in the same work, emulating scars, disconnected spellings, manumission documents and advertisements for the sale of black bodies.

The show also features works from the series Punishment Masks and Arturos. In the first, the artist uses portraits of his mother, Dona Tereza, to create, between negative and positive images, an emblem about the silencing imposed on black populations to this day.

For the making of Arturos, one of his most engaging series, Eustáquio lived among the remaining members of a Quilombo (Brazilian refugee slave settlement) in Minas Gerais state. Among multiple layers, we can glimpse the strength, resilience and beauty of the Afro culture that remained strong and pulsating – contrary to all historical attempts at erasure – in demonstrations such as the Congada (an Afro-Brazilian parade that restages a crowning of the king and queen of Congo).

The singular work of Eustáquio Neves leads us to reflect that for art to be able to move minds and hearts, demolishing false crystallized truths, it is often necessary for the artist, through his experimentations, to promote some implosions within the artistic language itself, to expand its frontiers and generate new points of view.